| |

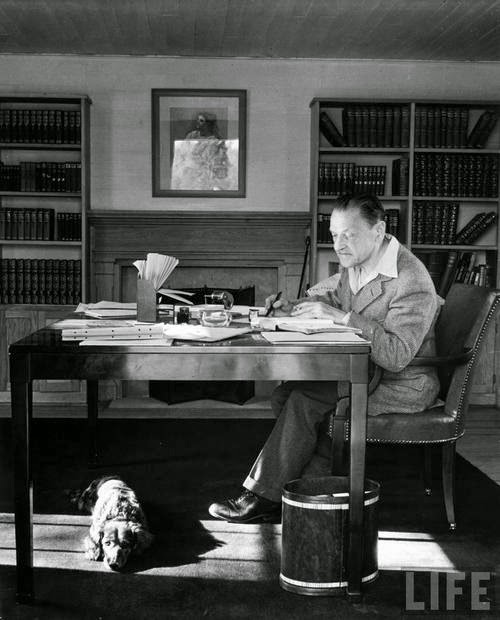

| W. Somerset Maugham at home, writing at his desk. |

"...the proper function of fiction is to tell an interesting story."

In 1952, W. Somerset Maugham said,

"The anecdote is the basis of fiction. The restlessness of writers forces upon fiction from time to time forms that are foreign to it, but when it has been oppressed for a period by obscurity, propaganda or affectation, it reverts, and returns inevitably to the proper function of fiction, which is to tell an interesting story."

These excerpts are from his Preface to the 1952 edition of "The Complete Short Stories of W. Somerset Maugham, Volume 2, 'The World Over'"

"I have written now nearly a hundred stories and one thing I have discovered is that whether you hit upon a story or not, whether it comes off or not, is very much a matter of luck. Stories are lying about at every street corner, but the writer may not be there at the moment they are waiting to be picked up or he may be looking at a shop window and pass them unnoticed."

|

| In the 1930s, Maugham was the world's highest paid writer. |

"He may write them before he has seen all there is to see in them or he may turn them over in his mind so long that they have lost their freshness. He may not have seen them from the exact standpoint at which they can be written to their best advantage."

"It is a rare and happy event when he conceives the idea of a story, writes it at the precise moment when it is ripe, and treats it in such a way as to get out of it all that it implicitly contains. Then it will be within its limitations perfect."

"But perfection is seldom achieved."

"I think a volume of modest dimensions would contain all the short stories which even closely approach it. The reader should be satisfied if in any collection of these short pieces of fiction he finds a general level of competence and on closing the book feels that he has been amused, interested, and moved."

|

| Maugham, in his office, Villa Mauresque, Cap Ferat, 1939 |

Maugham, W. Somerset. The Complete Short Stories of W. Somerset Maugham, Vols. 1 and 2. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1952.